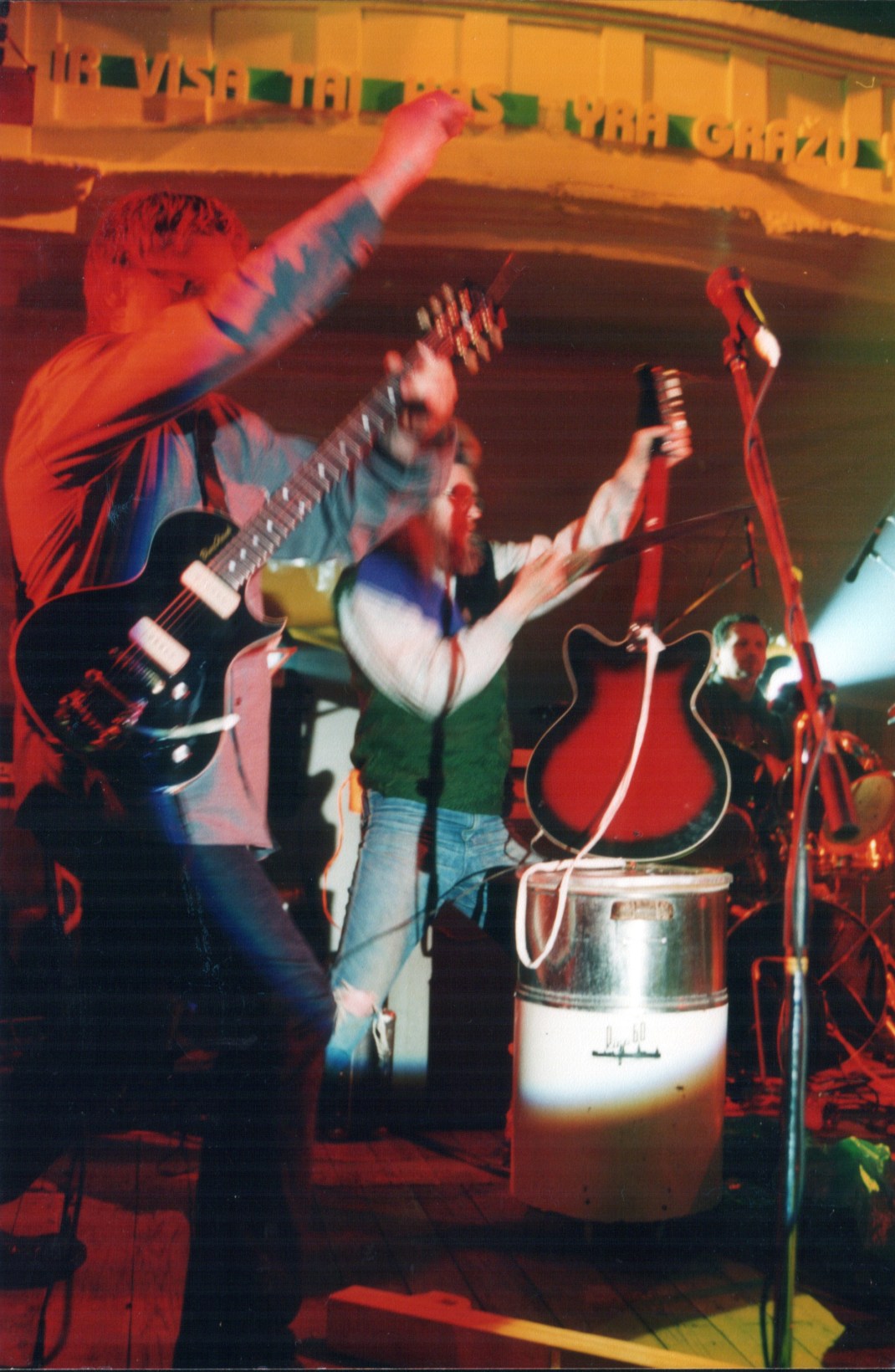

The interweaving stories of avant rock band Ir Visa Tai Kas Yra Gražu Yra Gražu, jazz improvisors Haruspic and radical film maker Artūras Barysas provide a window into Lithuania’s underground from the Soviet era to the present day. Lead image: Juozas Milašius, Artūras Barysas in 2000. All photos courtesy of the IVTKYGYG Archive.

On the bank of the Vilnia River, in the northern part of Vilnius Old Town, stands the Lithuanian National Culture Centre. This unassuming building is home to the Plokštelinė recording studio. The avant rock band Ir Visa Tai Kas Yra Gražu Yra Gražu (And Everything That Is Beautiful Is Beautiful, often shortened to Gražuoliai – The Handsome Ones – or abbreviated to IVTKYGYG) invited me here to witness the recording of Catastropicum, their first studio album in six years.

IVTKYGYG’s leader Artūras Šlipavičius aka Šlipas greets me warmly and immediately offers a glass of whisky, which, he tells me, helps to warm up the vocal cords and stave off the cold in the cavernous studio. The ceiling of the live room is adorned with triangular diffusers, hanging upside down like stalactites, which were installed during the Soviet era. The studio was formerly run by the state-owned record label Melodiya and is famed for having recorded acts such as the ska-infused post-punk band BIX.

Although IVTKYGYG formed in 1987, they had never recorded in this legendary space before, until a grant from the Ministry of Culture of Lithuania financed their new project. The sessions took place in early February 2022 amid rising geopolitical tensions in the region. When I arrive, the band are in the midst of recording a semi-improvised track called “Spletni” (“Gossip”). “There is so much gossip in Lithuania right now about the Russian tanks standing on Ukraine’s border,” Šlipas tells me afterwards. “There are so many emotions. We are recording this at a period when war could start next week.” Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine commenced two weeks after my trip.

Unlike their contemporaries Antis, who took an active part in the Singing Revolution of the late 1980s – a series of peaceful protests, which paved the way for independence of all three Baltic republics from the Soviet Union – IVTKYGYG claim never to have been overtly political. “It’s totally different with these guys,” says Radvilė Buivydienė, director of the Music Information Centre Lithuania. “Antis, they were mainstream. Everybody was talking about them. IVTKYGYG are the real underground. I think that IVTKYGYG is a gem for real diggers, because the context is very rich.” The Baltic republics had a relatively relaxed attitude to rock in the late 1960s and early 70s. The popularity of The Beatles spawned many bands who imitated their sound. Countercultural youth movements such as the khippi (hippies) were initially tolerated by the state, because the authorities knew that many Western hippies were ideologically opposed to capitalism. Estonians had access to Finnish TV and radio broadcasts and, in many parts of Lithuania, you could tune in to Radio Luxembourg. In the southwest of the country Polish TV and FM radio were also available. Rock flourished as a result and khippi youth would regularly congregate in the Baltic states during the summer, often travelling from all corners of the USSR.

This all changed in 1972, when 19 year old student Romas Kalanta burned himself to death in front of the Kaunas State Musical Theatre in protest against the Soviet regime in Lithuania. The police attempted to suppress his funeral, which angered the khippi community of Kaunas and the city fell into rioting. After order was restored, the authorities cracked down on anything seen to be countercultural. Men with long hair would be arrested on the streets and forcibly shorn. Rock was banned and many musicians gave up playing altogether.

Kaunas had been the temporary capital of independent Lithuania during the interwar period and was the country’s cultural centre before Kalanta’s self-immolation. After 1972, Vilnius became the bedrock of the nation’s culture. Until the early 80s, performing in a band meant playing state-approved compulsory repertoire in restaurants. Clubs only started reopening in the late 70s, as disco became popular. Slowly, amateur bands formed, but instruments and sound equipment were extremely hard to come by. The guitar body could be fashioned out of wood, but the strings, pickups and amplifiers had to be sourced from elsewhere.

Gedas Simniškis, Vaclovas Nevčesauskas in Poland, 1998

IVTKYGYG’s bassist Gediminas Simniškis aka Gedas tells me how they obtained bass strings during this time: “In our music school there stood an unused piano under the stairs. My brother and his friend decided to cut a few strings from it. I stood guard. Later, I asked my brother how they chose the strings – did they pick them out by their notes? He replied that they chose them by eye, judging by their thickness.” Payphones would be similarly vandalised, with the handset microphones appropriated and refashioned into DIY guitar pickups. Amplifiers were made from stolen loudspeakers. Everything was handmade. “We had essentially been playing punk rock on homemade instruments before they played punk rock in the UK,” Gedas recollects.

Gedas is a prolific bass player who also worked with Antis and the new wave group Foje, both of which achieved significant success in Lithuania in the late 80s. Around this time, he was listening to Billy Cobham and Frank Zappa (who has a monument dedicated to him in Vilnius despite having no connection to the city) as well as prog bands Emerson, Lake & Palmer and Yes. Šlipas also mentions Zappa as a principal influence along with Gong, Faust and Fred Frith.

This music came into their possession due to Lithuania’s large expat population. Relatives and acquaintances living in the West would often send LPs back home. These albums would then be sold, copied, and traded underground.

The most esteemed record collector in Vilnius was a jobless man called Artūras Barysas aka Baras. Bearded, shaggy-haired and bespectacled, he was well known in alternative circles. His apartment was stacked with rare books, vinyl and antique paraphernalia. It was a criminal offence to be unemployed in the Soviet Union, but due to Baras’s myopia he was able to claim disability. He sustained himself by selling rare books to collectors in the West and LPs to curious youth at home. He also made absurd experimental films, in the Fluxus style, that bring to mind the work of Lithuanian expat avant garde film maker Jonas Mekas. For example, the short 16mm film Tie Kurie Nežino Paklauskite Tų Kurie Žino (Those Who Don’t Know Should Ask Those Who Know), from 1975, has Baras playing a messianic figure who incites his disciples to fight among themselves before walking away from the carnage to the sound of Kraftwerk’s “Kometenmelodie 2”.

By the late 80s, the combined fallout from perestroika and glasnost shifted the cultural mood in Lithuania, not to mention the rest of the USSR. Bands began performing openly and organising festivals without fear of reprisal from the authorities. One such festival, Roko Maršas (Rock March), was initiated by Antis leader Algirdas Kaušpėdas. The festival toured various cities in Lithuania in the summers of 1987–89 and soon became a vehicle for the Sąjūdis independence movement, as documented in Giedrė Žickytė’s 2012 film Kaip Mes Žaidėme Revoliuciją (How We Played the Revolution). It was within this social context that IVTKYGYG began their journey. The morning after IVTKYGYG’s recording session at Plokštelinė, Šlipas picks me up in his green 4×4 outside the Aušros Vartai (Gates of Dawn), the historic entrance to Vilnius Old Town, to take me to his dacha, the countryside studio where he spends half of his working week. The vehicle is decorated with photos of IVTKYGYG’s members and logo. He wants to show me his paintings and, on the way, he reveals how he started making music. “I was a bard,” he explains, referring to the Soviet singer-songwriter genre. “Lots of complicated guitar parts. I had some fans, but not many.”

This was 1985, the era of the Soviet-Afghan War. Teachers were not required to serve in the army, so to avoid conscription, Šlipas took up a post teaching art at a school in Rudamina, a village just outside Vilnius. There he met jazz saxophonist Vytautas Labutis, who had performed alongside Vladimir Chekasin, Sergey Kuryokhin and many other influential Soviet jazz players. Labutis was also dodging the draft by teaching music. The two got together and improvised around Šlipas’s paintings, christening their project Haruspic (the name refers to an ancient divination practice that utilised animal entrails to make predictions).

Inspired by the Lithuanian symbolist Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis, Šlipas’s paintings depict surreal netherworlds inhabited by tortured figures. Posed in the Orthodox icon style, and often based on his own family members, these figures may be seen dining on eyeballs or, in a curious recurring motif, pickled cucumbers. The facial expressions of the sitters are distant, as if mourning a lifetime of mistakes and missed opportunities. Haruspic’s music reflects these themes on tracks like “The Flood”, in which two flutes, played by Šlipas and his wife Ara Šlipavičienė, intertwine with Labutis’s violin in a pseudo-medieval danse macabre. “Music like that you can only listen to once a year,” Šlipas says. “It’s very conceptual. You can’t drive, dance or drink wine to it. You have to look at the paintings and think.”

Running in parallel to Haruspic, but not directly connected to visual art, was IVTKYGYG. Despite having no musical ability, Baras was encouraged to start playing with Šlipas by pioneering punk musician Nėrius Pečiūra, who also drummed with IVTKYGYG for a short time. The band’s early work mixed energetic post-punk with accents of sonic eccentricity reminiscent of Pere Ubu or The Residents. Rehearsals took place twice a week, in the small basement of a residential house, with reel-to-reel recorders left running. These lo-fi recordings document a band on a vector separate from their contemporaries. Gedas tethered the band with his Peter Hook-like bass riffs as Šlipas’s raw guitar seared across the sonic spectrum. Baras, meanwhile, yowled lyrics appropriated from newspapers or other found materials. On “Eiti Eiti Eiti”, for example, Baras repeats, “Eiti eiti, dirbti dirbti, dar susitvarkyti” (“Go go, work work, sort it out afterwards”) – an ironic mantra ridiculing the Soviet obsession with labour as a symbol of economic citizenship.

Their self-titled debut, affectionately known as The Yellow Album on account of its cover art, was an underground hit when released on cassette in the early 90s (first under the patronage of Berlin’s Radio Marabu and later reissued by Lithuania’s Bomba Records). Recorded between 1989–91, the album reflects IVTKYGYG’s energetic early stage shows. The band would perform no more than a few live takes onto primitive equipment, before committing to a recording everyone could agree on. This resulted in an uncompromising sound that referenced the group’s appreciation of experimental music, while infusing the songs with a punk-like urgency. The album standout “Šunparkis” (“Dogpark”) references a rundown yard situated behind the Presidential Palace in Vilnius. The place was popular with punks and street drinkers, and was frequented by Baras himself. The song became a hit, particularly with students, and still elicits a jubilant response from the audience when performed today, due to the infectious riff Šlipas plays on his modified rubab.

Baras was a charismatic frontman, but the gigs were unpredictable. Gedas remembers one concert where the small stage had been extended by placing tables end to end. “For some reason, there was one table missing, which created a gap,” he says. “Baras was walking backwards [on the stage] and didn’t notice there was a table missing. He fell right into that hole.”

Another story recounts one of IVTKYGYG’s notorious washing machine concerts. Inspired by Fred Frith’s experimental guitar playing, Šlipas realised that everything had a sound potential, and all you needed was a microphone to amplify the signal. The band set up four Riga brand washing machines and put various objects, such as tennis balls, inside their upright cylindrical drums, creating a disorientating rhythmical din. One year, at the Muzyka W Krajobrazie (Music In The Landscape) festival in Poland, IVTKYGYG were performing one of these experimental sets. Baras’s machine refused to switch on. Eventually, the frontman realised it wasn’t plugged in, but instead of finding a spare socket, he unplugged an extension cable connected to other equipment and cut power to the PA. Perhaps echoing an anti-hero from one of his own films, Baras revelled in the ensuing chaos.

Baras drank heavily, before shows and in everyday life. His addiction eventually led to him being incarcerated in a “therapeutic labour dispensary” (a state-mandated rehab centre for problem drinkers) and inevitably caused tensions within the band. Ara Šlipavičienė, who played various instruments in IVTKYGYG before largely leaving the band to concentrate on her family and career in insurance, recalls that towards the end of his life, the frontman’s drinking became increasingly problematic.

“He was, at that time, very ill,” she recalls. “We had a really important gig and we guarded Baras for three days so that he wouldn’t drink. Still he demanded it. We gave him water, but told him it was vodka. He couldn’t tell the difference. We all thought it was funny at the time but, of course, it isn’t funny at all.”

In one of his last films, Suvokimas (Perception), Baras plays a man possessed by a woollen blanket – a metaphor for the perception-altering qualities of alcohol – who murders an artist in his studio. He is later arrested but released without charge. The short film is at once a delirious allegory of alcoholism and a self-reflective look into how addiction can destroy creativity. “Half the film was shot in my studio,” remembers Šlipas. “[Baras] wanted to show how seriously ill he was. How hard [alcohol addiction] is.”

Baras died in 2005, the night before IVTKYGYG were due to record their washing machine project. The band paid their respects with an art action near the Neris River. They lit a fire inside of Baras’s washing machine, burned the scarf in which he died, and threw the washing machine over a bridge. Says Šlipas: “Baras once said that he wanted his ashes to reach the White Sea. We felt that in this way, it will happen.” During one of Baras’s extended spells in state-enforced rehab in the mid-90s, Šlipas decided to change the band’s direction. By this time, they had already begun experimenting with different forms, amassing a rich archive of so-called Birthday Tapes.

These recordings ranged from standard rehearsal recordings to quirky birthday songs composed for each of the band members. A horn section was added, a singular concept developed and the arrangements began displaying elements of progressive rock, jazz and esoteric folk music.

Released in 1996 by Bomba Records, IVTKYGYG’s second album Linkėjimai Falkenhanui (Greetings To Falkenhann) is considered by Šlipas and Ara to be the band’s finest work. The album is informed by the horrors of the First World War and its title references the Prussian general Erich von Falkenhayn, the commander responsible for deploying poison gas on the Western Front. The album is composed of nine tracks, most of which are instrumental. The saxophones (played by Artūras Martinaitis, Darius Kodikas and Vytautas Labutis) often lead the way, cutting through percussive undergrowth or repetitively raging against IVTKYGYG’s rhythm section. With the lead vocalist largely absent, the interplay of melody and texture became principal concerns for the group.

The credits list 11 personnel playing a wide range of instruments that include some unusual sounding objects: kitchen kerbs, kaziukas, haruspik. In the studio, Gedas shows me a surviving haruspik, one that the band still perform with today. It is fashioned out of a long metal cylinder that eerily resembles an amputated tank gun. Categorically, the instrument sits somewhere between an electrified tube zither and a percussive outsider art sculpture. The haruspik was built by the band themselves and they consider it to be their signature instrument.

“For music lovers in Lithuania, this project passed with a bang,” Šlipas says of the album. “It’s completely different, because I was different. The band needed to evolve. It’s my masterpiece.” On his return from rehab, Baras was angered to find that Šlipas had recorded the album without him. What was he going to do on stage, if there weren’t any songs to sing? The two fell out, but eventually reached a compromise by having Baras viscerally shout “Falken-hann” over and again on the title track. Arranged in 3/4 time, the sinister song closes the album, and is described by Šlipas as “the final waltz – the waltz of death”. Surprised by its power, Šlipas was moved to tears listening back to the finished work for the first time.

Live, the band’s theatrics are reminiscent of Peter Gabrielera Genesis. In contrast to the British prog rock band, however, IVTKYGYG’s staging is laced with irony. Footage from their 25th anniversary concert in 2012 shows Rimas, Šlipas’s brother – a stained glass artist and collaborator who designed the band’s logo and wrote “Šunparkis” – wearing a yellow hazmat suit and gas mask. The costume evokes the spectre of Erich von Falkenhayn and the spirits of those who fell in conflict as a result of chemical weapons. Rimas mimes sawing off his own forearm with a bow-like object, while Ara and Arvydas Makauskas aka Makys (the band’s post-Baras vocalist) exchange rhythmic scat lines.

The band’s work is steeped in ambiguity and it can be difficult to unpack the messages behind their songs. IVTKYGYG’s percussionist and archivist Robertas Kancius sent over some translated lyrics. “Aš Aš” (“That’s Me, That’s Me”), from the 2016 album Paradas (Parade), is a bossa nova-like ska fusion that derives its lyrics from tabloid newspapers and celebrity magazines. “It’s a collage of the actual headings from the yellow press,” explains Kancius. “X did this and that, Y had dinner from plates made of chocolate, Z opened a bottle of champagne with a sword. We just skipped the names and left the actions only.” The result is a critique of the celebrity-driven personality cult. “Saldus Saldainis” (“Sweet Candy”), which appears on the 2002 album Lavonai (Corpses), treads similar ground. The only lyrics you hear are “saldus saldainis įstrigo mano gerklėje ir gargaliuoja” (“the sweet candy got stuck into my throat and gargles”). Kancius says: “[It] looks like nonsense, but that sweet candy can be anything from pop culture (in the worst sense of this word) or politicians’ promises, to anything the masses are fed to be stupid, happy and obedient.”

Their most problematic song is “Pigūs Norai” (“Cheap Desires”), the recording of which I witnessed at the studio. Although it was written in response to China’s blockade of Lithuanian goods (a measure intended to overturn the Baltic state’s ties with Taiwan), and is clearly engaged with a postmodern play on meaning and meaninglessness, the track’s execution comes across as a reactionary cultural appropriation. Ara sings lyrics mediated by an online translator in a faux-Chinese accent, while Šlipas’s melodic motifs imitate Chinese folk music.

Despite the track title’s apparent critique of globalisation, I ask Šlipas to clarify his intentions. He collects his thoughts before replying: “I lived for three months in the USA, in New York and Chicago. I exhibited my multimedia works, drank wine with [Jonas] Mekas. I wanted to buy some tableware for my dacha, but everything for sale was ‘made in China’. You begin to understand that maybe your brains are made in China, perhaps your ears are too. Do you hear what you’re supposed to? All the trains have been blocked by China, because a de facto Taiwanese embassy was opened in Vilnius. Everything is really bad in Lithuania currently. All the products, everything is stuck [at customs].”

In 2002, a few years before his death, Baras was invited to screen his films and read poetry at The Horse Hospital in London. He was received well by the Lithuanian expat community who attended the event, and was introduced to John Balance and Stephen Thrower of Coil, whose work he greatly admired. The event’s organiser David Ellis later played a significant role in bringing Baras’s work, as well as the music of IVTKYGYG, to a wider audience. Strut Records is releasing a compilation chronicling Ir Visa Tai Kas Yra Gražu Yra Gražu’s idiosyncratic compositions. The album, co-curated by Ellis and Strut founder Quinton Scott, taps into the band’s archive, shining light on long out of print recordings, recontextualising their better-known works, and making some of their rehearsal tapes public for the first time.

Baras’s films have also been restored and made public. Dovydas Bluvšteinas (founder of Zona Records, the first independent label in the Eastern Bloc) and Robertas Kundrotas (co-founder and former editor of the experimental music magazine Tango) undertook the project, for which Ellis was a creative advisor. With the help of Baras’s son, video editor Vytis Barysas, they began digitising the prints. The soundtracks to the original films contained unlicensed music collaged together. To get around the issue of copyright, several contemporary Lithuanian artists were asked to contribute new compositions.

How were the participants selected? “At the very least, they had to know who Baras was,” says Kundrotas. “Better still, if they knew him. They’re all serious artists: underground musicians, noiseniks, experimentalists.”

Rimas Šlipavičius, Ara Šlipavičienė and Gedas Simniškis, circa 1990s

Baras: Contemporary Lithuanian Composers Scores To Artūras Barysas Short Films 1972–1982 was released on Zona Records in April 2022, and features 15 tracks from contributors such as Gintas K, McKaras and Arturas Bumšteinas. Many of the compositions feature ambient soundscapes, drones and field recordings. For example, Bumšteinas, who soundtracked Romas, Renata, Rimas (1977), blended the sounds of cicadas with organ drones and shortwave radio broadcasts. Coupled with saturated visuals of three friends swimming in a river and picking flowers in the nude, the result is a carefree impression of summer. Haruspic also contributed music for Tas Saldus Žodis (That Sweet Word, 1977) and Intelektuali Popietė (An Intellectual Afternoon, 1982), which can be viewed, along with the other restored films, on the website of the Lithuanian public broadcaster LRT. Towards the end of my visit, I’m invited to preview Balti Sparnai/ White Wings, Haruspic’s first album in two decades. Labutis’s studio is located on an industrial estate in the Žirmūnai district, on the north bank of the Neris. Erected in the Soviet era, the buildings in this complex all contain underground bomb shelters, later converted for alternative use. Labutis’s basement bunker, which he has occupied for 16 years, is filled with various instruments, electronic equipment, cables and computer monitors. The walls and ceilings are covered with carpet tiles to dampen the sound. Šlipas drives me here, and after shutting off the outside world with a steel blast door we listen to some key tracks together.

This record is very different from their earlier albums Haruspicija and Lethe. Whereas before Haruspic leaned heavily on free jazz and folk, this time musique concrète, samples and electronics all make an appearance. On “Menui Menas/Art For Art’s Sake”, Bluvšteinas recites a tautological manifesto inspired by the Italian Futurists. His voice is transformed with a vocoder, perhaps a nod to David Lynch’s “Strange And Unproductive Thinking”, before being chopped, repitched and pelted with disorientating dubstep bass drops.

Elsewhere more traditional rock structures emerge, as on “Manjana/Mañana”, but Haruspic subvert old tropes with nonsensical ironic humour. Labutis cites Russian musician Sergey Kuryokhin as an influence, recalling one concert in which a horse was brought onstage. It defecated next to the string quartet and was led off again. Kuryokhin’s infamous televised hoax Ленин — гриб (Lenin Was A Mushroom, 1991) also impacted this project. In the 60 minute interview, the po-faced composer reasoned, with reference to ‘evidence’, that the Bolshevik revolutionary and founder of the Soviet Union was in fact a mushroom. I ask about the change in direction. “It’s radical and we’re conscious that it’s different,” admits Labutis. “It’s not that it wasn’t working before, it’s just that a lot of time has passed since our early recordings.”

The worlds of Haruspic and Ir Visa Tai Kas Yra Gražu Yra Gražu have cross-pollinated over the years, the projects imbuing each other with avant garde ideas or more straightforward rock freakouts. In many ways, Šlipas is a modernist, but uses postmodernist techniques to achieve his aims. “It’s no coincidence we are named Haruspic,” concludes Labutis. “Because divination is what we do. We never give an answer, only provide associations. We know nothing ourselves.” ● The self-titled compilation Ir Visa Tai Kas Yra Gražu Yra Gražu will be released by Strut Records in May 2025

Ilia Rogatchevski

Originally published by The Wire, October 2024