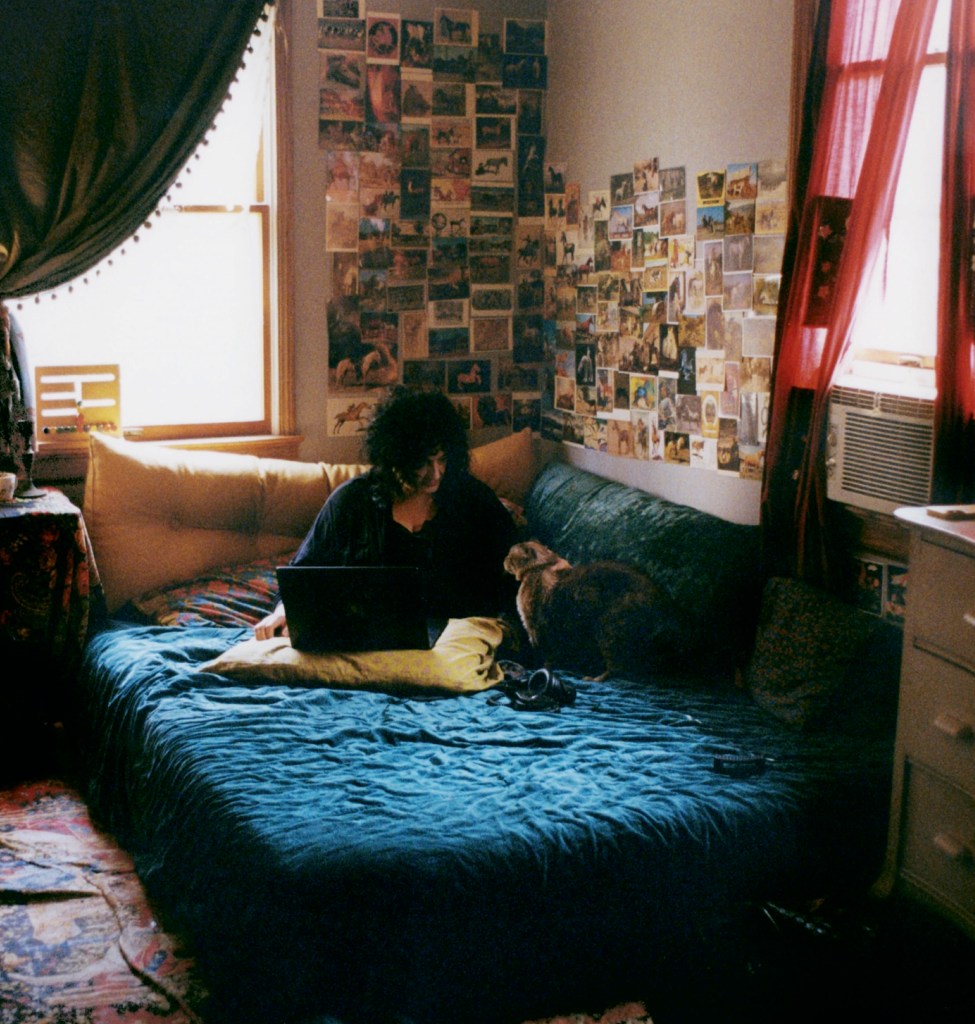

The composer and field recordist draws on a painterly sensibility to layer loops and samples into documentary narratives that are startling, funny and human. Photography by Ashley Markle

Poised over a laptop at a recent Cafe Oto show in London, Vanessa Rossetto pulls up spliced recordings of disparate voices, looping ephemera and snatches of incidental melody. She gestures and lipsyncs to the samples, layering clips on the fly and improvising new transient spaces from unremarkable fragments of time. Prior to her 2025 European tour, Rossetto had only played a handful of shows, even though she’s been producing music since the late 2000s. “I haven’t played live very much and I’m still working that out,” she confides over a video call from her Staten Island home. “Some elements are more constructed, some are not. In Lithuania, [April’s] Jauna Muzika festival had the theme of the amateur and so I sourced recordings of people singing their favourite songs. I made a backing track and set mics up so that people in the audience could come up and sing. I was ready to sing the whole 30 minutes myself if I had to, but every time I looked up there were different people doing it.” The recordings created on this tour will most likely see publication next year as The Professional, a double album on the Erstwhile Records imprint ErstSolo, which will “explore the idea of being put into that sort of situation, as an untrained and inexperienced practitioner, and the humorous situations that would undoubtedly ensue”.

The original meaning of amateur is a lover of something, and Rossetto’s journey in composition reflects this. Initially trained as a painter, she began working with sound almost 20 years ago by habitually recording her surroundings and constructing epic compositions from hundreds of layers. Her latest release Pictures Of The Warm South spans 142 minutes across two CDs. It’s her longest work to date, but the soundworlds present on the recordings are far from random, focusing on Rossetto’s relationship with her mother Toni. “She was liquidating her possessions and selling the house so that she could move into an apartment complex for older people. For almost four months I was helping her do this and recording the whole time. She moved to Alabama and then passed away. I went there and recorded her funeral at the apartments.”

Toni’s monologues are woven into an impressionistic documentary featuring street musicians, traffic, commercials and domestic minutiae that together underpin the traces that our lives leave behind. Listening to Pictures Of The Warm South is like being a guest in a strange house. You surreptitiously wander into different rooms and examine the objects there, which together form a portrait of the host, their tastes and personality. Familial complexities inevitably come into play, as in the piece “pool water, salt water, and the water in your head” in which Rossetto is heard crying and her mother berates her for it. Towards the end, “the chapel” captures the ritual of mourning at Toni’s funeral. Rossetto’s eulogy encourages those in attendance to dance rather than grieve. Even though the ones we love leave us, life carries on.

Rossetto’s mother is also the central voice on the 2019 album You & I Are Earth, in which she recalls memories of being a young girl during the London Blitz. The Actress, from 2022, is also dedicated to her. “She was so influential to me in ways that she will now never realise,” Rossetto explains. “I don’t know if she understood what I was doing, if it made sense to her as an artform. She found it confusing that I recorded things and put them together, but the whole reason I went on the European tour was because when I was at her house helping her pack, people from the Archipel festival in Geneva contacted me. I wasn’t sure if I should go. She was like, ‘You have to do this.’ She made me promise that I would go.” Rossetto grew up in New Orleans and considers the city to be pivotal to her development as an artist, not only because of its rich musical heritage but its outdoor culture. Toni sold paintings on Jackson Square and Vanessa spent a lot of time in the French Quarter, which is the centre for tourism, Mardi Gras, bar culture and street life. “As a kid I was down there all the time with her. She hung her paintings on a fence and sold them like that. I remember waiting for her to pack up and listening to all these sounds overlapping. When I got older, I would go walking and listening, seeing all this crazy behaviour – people go wild there. That really influenced me and I don’t know if I appreciated it as much at the time as I do now in retrospect.”

Her mother would set up an assembly line in their kitchen, and Vanessa helped by colouring the paintings. Seeing that it was possible to make a living from art drove Rossetto to study it herself, first at the University of Texas at Austin and later at Tulane University in New Orleans. Despite being immersed in Austin’s slacker scene and being into “ridiculous out there stuff” like Butthole Surfers and Scratch Acid, Rossetto’s transition towards working with sound wasn’t immediate. “At the time, I was really just trying to paint well but I was interested in performance art too. I had this microcassette recorder and was trying to record my entire inner monologue. I wish I still had the tapes.”

Rossetto had some gallery shows, but became increasingly frustrated with the limitations of painting as a medium. She began producing autobiographical comics and briefly considered making films. “I wanted to deal with narrative and time. Those were two things that I didn’t know how to approach. Film making seemed too complicated and intimidating. Narrowing it down to sound was like taking a slice of that and isolating it, which seemed more approachable to me as someone with no musical background.” Having friends in “quote unquote weird bands” gave Rossetto access to instruments and recording equipment, but she didn’t start making music in earnest until her late thirties. “I was drifting around and trying different things. It took me a long time to attempt anything with sound. I had friends with mixers and started recording whatever was happening in my house – just leaving it running and recording my activity or lack of activity – and making things out of that. I was aware of field recording but not its possibilities, other than documentary capture of an instance.” Rossetto’s first musical project was Catrider, a duo with the Australian musician Michael Donnelly. Their self-titled album was recorded in 2006 in a few days while Donnelly was staying in Austin. “From Mirrors Are Oceans”, which appears on the Music Your Mind Will Love You label’s 2008 Hand-Rolled Oblivion compilation, is awash with a claustrophobic combination of scratched objects, pawed strings and reverb. The same CD-R album also features “Arnold School 1” by The Mighty Acts Of God. This early solo project of Rossetto’s saw her experimenting with her housemate’s instruments, layering and processing them into anxious soundscapes, a method that led her to embrace chamber instrumentation more widely across her work.

Around this time, she was also turned on to the I Hate Music (IHM) forum by the composer Steven Flato, whom she met on MySpace and collaborated with as part of the improvisation duo Hwaet. “I was finding out about all these things [on IHM] and the floodgates opened to all the possibilities of what could be done. I started just making things, fulfilling something that painting had not for me. Something clicked at that point.” A wide spectrum of experimental music was discussed on the forum including noise, classical and musique concrète. It proved to be an invaluable resource and a pathway to collaborations with likeminded artists in different corners of the world. Over the years these have included Lee Patterson, Lionel Marchetti and Moniek Darge.

Imperial Brick, Misafridal and Whoreson In The WIlderness, a trilogy of albums released on her own Music Appreciation label in 2008, largely discarded effects and documented Rossetto’s raw droning improvisations on viola. Each album bore a minimalist black cover that suggested the sparse sounds within. It wasn’t until Dogs In English Porcelain, released the following year, that Rossetto hit her stride with measured and intentional composition. Constructed over the course of ten months, the 41 minute piece combined countless field recordings of domestic activities and aural snapshots from daily life. “Dogs In English Porcelain was the first one where I feel like I was using the actual form that I’m still using now: edited and augmented field recordings. When I first started learning how to operate a recorder and software, I would begin with a substrate layer – the length of whatever I wanted the track to be – look at where things were happening and build around those. I was trying to figure out a process of how to make things coalesce.” Dogs In English Porcelain caught the attention of Graham Lambkin, whose Salmon Run album influenced Rossetto’s early work. Lambkin asked her to produce a 7″ for his Kye label, a project that evolved into 2010’s Mineral Orange album. Feeling uncertain about what shape the tracks should take, she sent unfinished compositions to Lambkin for feedback. “He had a lot of input on that, because, at the time, I was very unsure about what I was doing. I was probably a pain in the ass sending him partially done things. I would never do that now!”

Two more Kye releases followed, 2012’s Exotic Exit and 2014’s Whole Stories, both of which intensified Rossetto’s method of splicing hundreds of recordings and carefully layering them to construct new narratives from the resulting juxtapositions. “That’s why it takes me a long time to make them,” she says. “I actually work often and for long periods of time, but some of the files are ridiculously huge. I use Audacity too and that’s maybe part of it. It’s actually analogous to the way I used to paint, because I mixed a lot of medium with my paint. The layers were translucent so you could see down into the paintings. I feel there is some relation there.”

Exotic Exit saw her expand the sonic palette to include violin, cello, dulcetina and glockenspiel on top of recordings from quotidian settings, language tapes and incidental conversations. The material developed from a live collaboration with Lambkin for the 2011 edition of the AMPLIFY festival in New York, which was organised by Erstwhile founder and IHM alumnus Jon Abbey. Rossetto used the live performances leading up to AMPLIFY as an opportunity to mould the material into what Matthew Revert referred to in a 2013 article for Surround as “a canvas where fragments of life are assembled into fictions”. Revert, a writer and multidisciplinary artist based in Melbourne, is Vanessa’s most frequent collaborator and life partner, even though they live on different continents. Revert was also a contributor to IHM, but their paths crossed properly during the making of Exotic Exit when Rossetto commissioned him to create the album cover, after being impressed by his book jacket designs.

“We met online,” she recalls. “We started working on things together and he came to visit me when I was performing at the Kye showcase at ISSUE Project Room [New York, 2014]. He was the secret guest and we did a duo set together. While he was here we were recording the whole time, quickly assembling an album. I would say my biggest influence is probably Matthew because he’s such a brave performer. He is creatively free and knowledgeable about a wide variety of artforms.”

Earnest Rubbish, the result of these sessions, came out on Erstwhile in 2016. Commissioned by Abbey, most Erst duos bring together musicians who would not have played together before and perhaps don’t even know each other. By this point he had already put out Severe Liberties, her collaboration with Kevin Parks, and liked what Rossetto and Revert sent in, pairing their release with Christian Wolff and Michael Pisaro’s Looking Around.

Earnest Rubbish, released in 2016, and its 2018 follow-up Everyone Needs A Plan, are looser in the way they combine ephemeral sounds when compared with Rossetto’s other work. The latter album in particular drifts from hissing drones and swollen strings to fractious synthesizer tones. Across 75 minutes, Rossetto and Revert’s late night voice notes drop in and out of the liminal soundscape. They suggest a scripted but elusive narrative that filters through as you slip into semi-consciousness while falling asleep to the radio. Rossetto thrives on longform pieces and when I mention that her work is perfect for the medium of experimental broadcasts she lights up. “I’ve actually been thinking a lot about radio plays and things of that nature,” she enthuses. “That’s one of the things that influenced the concept of mine and Matt’s next one. I have a lot of ideas but I don’t want to give them away. It will have ‘vignettes within a framework’ and follow the trajectory of the other two.” Rossetto is fastidious about planning which elements appear where in a given composition, sitting with a notebook and mapping them out. “Sometimes I draw, not a graphic score, but the shape of where I want things to be. I have really particular ideas about that, which has pissed off some collaborators before. There have been people who said, ‘Oh, you just put stuff wherever!’ as if I’m just throwing a bunch of things in together, but it’s all very intentional. Every single bit of it is individually placed to a microscopic degree.”

An example of her attention to detail can be heard on The Way You Make Me Feel and Erased De Kooning, both created in 2014 but released a few years apart. These works are composed from what Rossetto refers to as interstices or “the silences between deliberate acts”. Inspired by the Robert Rauschenberg artwork, the latter album sourced its sounds from the Experimental Music Year Book, which between 2009–19 published an online repository of works by composers working in experimental music. But The Way You Make Me Feel came from a more personal place. “I suffer from lifelong depression and anxiety and I was going through a very bad period around that time. I was also paradoxically going through really wonderful things but I was not allowing myself to experience them. I was removing myself from the possibility of being happy because I was so ill. In trying to remove most of the intentionality and leaving only the interstices in those recordings, I was trying to express that.”

These sentiments are evident in pictorial form, too. Rossetto’s Bandcamp bio jokingly claims that she is a horse. This has flowered into a meme among her fans and resulted in many horse-related gifts over the years, some of which decorate the walls of her apartment. Revert’s cover design for 2022’s The Actress depicts an erased horse. With its ghostly outline lingering in a field, this image can also be interpreted as the subconscious removal of self – although Rossetto maintains that she simply preferred the background to the horse. Over time Rossetto has become more present in her pieces. Her voice appears regularly, from Exotic Exit through to her sonic collaborations with Revert and beyond, and anchors the ear at critical points in the narrative. “This Is A Recorder”, which takes up the first side of Whole Stories, is a good example of her authorial presence. “I was in New Orleans during Mardi Gras. People were all drunk and uninhibited and I had my recorder with a big fluffy windscreen on it. This guy came up to me and asked what it was and I was like, I record things, cut them up and reassemble them so that they have some narrative structure. This is the point where I felt like I was making my intentionality clear. I was trying to make sense of the world and that’s still what I’m trying to do.”

Rossetto continues that she would like to go further by forcing interactions and being more active in public to see what happens. When I bring up that the recordist’s presence can often be seen as taboo, particularly in wildlife recording, due to the perception that it undermines the purity of the natural environment, she responds: “I have a lot of respect for nature recordists but if there are no people, I’m not interested. That element is important to me. I want to go where there is interaction and human life. What’s interesting about most artforms is seeing the hand of the creator in them. Otherwise it’s sterile to me. I love street performers, cars passing by, getting in and out of Ubers with different songs on the radio, doors closing and delineating one space from another. I like the mistakes and bumped recorders in your bag. The unintentional is sometimes the most interesting.” ● Vanessa Rossetto’s Pictures Of The Warm South is released by ErstSolo

Ilia Rogatchevski

Originally published by The Wire, July 2025